WINNER – Heating & Ventilation News Award 2019 (Retrofit of the Year)

Bibury Farm – a cluster of handsome Cotswold stone buildings – sits high on the Cotswold plateau, with the chocolate-box Cotswold village of the same name nestling below. And it was farming – wool production in particular – that created the wealth that built the handsome Cotswold churches and manor houses – and also, the much-photographed Arlington Row cottages of Bibury itself.

Farming has changed and changed again since the medieval heyday of Cotswold wool. Farm buildings erected to store hay or wooden carts, or house a small number of animals, are no longer usable for their original purpose – hence the natural desire to turn them into buildings for people to live in.

But while an old cottage in a village at least has the merits of being relatively small, and with a good chance of a sheltered location, Cotswold barns like those at Bibury farm tend to be in exposed locations, and barn conversions are all too often cold, cavernous, draughty and nigh-on unheatable.

Bibury Farm was built all of a piece in the early to mid 19th century, as a ‘model farm’. Despite being forward-looking at the time, the buildings were soon overtaken by yet another revolution in farming, and in recent years were only being used to store bits and pieces and a couple of old cars.

As owner George Phillips explained: “We were only really maintaining the roofs to keep them watertight – there was no longer a use for them. But they could potentially be an asset. Our main intention was to to keep the barns in our ownership, and long term lets (ASTs) would not achieve the income requirements in order to service borrowings required to complete the project.

“From a business point of view, because the Cotswolds is such a popular holiday area, it looked as though holiday lettings would be the best route. Staycations are becoming a big thing now with the lower pound, and people come to the Cotswolds from all over the world.” Additionally, there are a lot of wedding venues in the area, increasing the demand for accommodation.

All of this pointed to a high-end, luxury conversion, and Jonathan Nettleton of Blake Architects and Greengauge Building Energy Consultants were taken on, along with interior designer Pippa Paton, to design something really first-class.

One of George’s main concerns was that the holiday lets should be comfortable – really comfortable: “Old stone buildings can be very cold, and I was worried about how people coming from warm houses in London would perceive them.” This was a valid concern, Hannah Jones from Greengauge agreed:

“I’m familiar with Cotswold barn conversions where you rush from one warm spot to another and the rest of the building is only 12 degrees. That would not do for here!”

Trying to heat a draughty, stone-walled building to a liveable temperature can often mean you end up running the heating at a very high temperature – leading to hot spots and cold spots, as well as high bills, Hannah explained “We wanted to avoid this, and make the spaces comfortable and cost effective to run.”

But of course building conversions carried out in an AONB such as the Cotswolds are subject to strict planning conditions – and the barns at Bibury Farm are also within the curtilage of a listed building (the old farmhouse).

While there was a more modern Dutch barn in the cluster, the other, stone buildings such as the threshing barn and cart store were very traditional.

Jonathan Nettleton worked hard to ensure the character of the buildings was preserved as far as possible: “The buildings divided themselves quite neatly to make the five dwellings without needing to subdivide them – we have kept the existing boundaries and you can still read the original buildings easily.”

“Because of the planning constraints, we could only make limited changes outside. But the conservation team at Cotswold District Council were very helpful and proactive.”

Hannah agreed: “We had a really good meeting with the planning team. They were keen to see low CO2 emissions and we explained that we would favour the approach of insulating to reduce energy demand. The conservation officers were prepared to let us insulate internally.”

Jonathan added: “We wanted to use materials that would allow moisture to come and go as before, so we have used a lime parge and wood fibre insulation, which should work long-term. We had to justify this to building control but we believe this will do less harm than sticking on impermeable foam boards.”

Lowering heat loss through the fabric it made it possible for the bulildings to be warm throughout. And the fabric first approach tied in well with the high end specification, Hannah Jones added.

“If we insulated and paid attention to airtightness, and installed MVHR, we could get the heat demand low enough to make it possible to heat via underfloor heating – which fits in so much better with the interior design in a luxury project like this. Without insulation and improvement to the airtightness, the only way to keep it warm would have been to use lots and lots of radiators, which would have spoilt the internal appearance.”

Greengauge had to take great care in balancing the requirements to preserve and show off the original fabric, with the desire to keep the occupants warm and cosy.

The desire to preserve the barns’ character also meant leaving stone walls and the old timbers visible where possible. Many of the internal stone walls are unplastered, and timbers are exposed under cathedral ceilings. The distinctive stone columns of the cart store also remain fully exposed – cannily separated from the warm interior by running the high-specification glazing entirely behind them.

The team were able to achieve a good improvement in fabric performance, even though they restricted the insulation depth to 60-80mm. “We did this because we could not be completely thermal bridge free within the constraints of the historic building,” Hannah explained. “To insulate more deeply would have required much more intervention because thermal bridges, which are really hard to deal with in this sort of situation, start to dominate – For example, we considered cutting through beams to create thermal breaks – which we wouldn’t have been allowed to do. It was important not to reduce the temperature of the masonry too dramatically.”

Similarly deep interventions would have been needed to get to Passivhaus levels of airtightness, so this had to be ruled out. Nonetheless, especially given the exposed location, improving airtightness was crucial to the final performance. The airtightness has been significantly improved through installing the new floors, and by the internal insulation, which has a levelling render behind it, and internal wet plaster on top.

“In a lot of areas the rafters are covered completely, but where they exposed, the penetrations of the timber frames and purlins inevitably create weaker points: where possible the builders taped between the timbers and internal insulation, to minimise air leakage,” Hannah says.

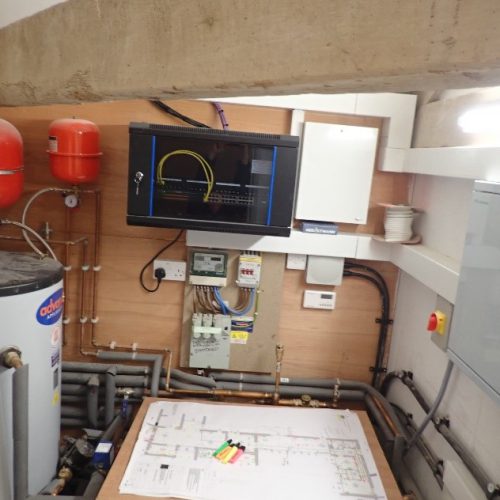

The cluster of buildings could have lent itself to one centralised plant room for heat. But everyone was keen to avoid a massive boiler if possible – with no gas in the rural location, this would have probably meant oil, which can be both noisy and smelly, as well as requiring an unsightly tank. The preference was for individual heating systems, to keep open the option to sell the barns as private homes in the future.

Happily, reducing the heat load enough to permit underfloor heating opened the door to low -carbon heating: the low heating temperatures required meant it was possible to opt for a heat pump – further reducing emissions – “so that all tied together really well,” Hannah said.

George agrees: “The planners were looking for a low-carbon system, and it was also desirable in terms of the holiday let that guests can know it has a low carbon footprint. We looked into various approaches including installing solar panels next door, but heat pumps worked out as the best in the end.”

Air source heat pumps were considered, but rejected. It would have been quite difficult to integrate these nicely into the development, Hannah explained. “There would potentially be issues of noise where dwellings had just a little courtyard, and ASHPs themselves aren’t the most attractive.”

“We talked to Kensa and established that we could use a communal ground-source array feeding individual heat pumps. However, it would also have been difficult to fit in a horizontal loop on site, as it would have had to be very large, and the only available open space within the development was reserved for potential later development; and the surrounding fields are managed under a different business.

“So instead we went for boreholes which would be fitted under the existing pathways, so it’s all very neat.”

It was expensive though – as George says: “We had to drill 13 boreholes, which was quite an undertaking – but we were able to get help from the RHI, including with the capital cost”

The heat pumps have to provide more than just space heating. People in luxury holiday accommodation use a lot of hot water – and it’s also possible that it would all be needed at the same time: when people come in from their country walk, or are all getting dressed up together.

As Hannah explains, “There is a lot of hot water storage, and we have also added immersion heaters, to ensure there is instant top-up if there is a big party all wanting to take showers at once.

“Most of the units have two hot water tanks, to minimise the pipe runs and the amount of hot water circulation needed – the buildings are very long and thin.”

It is important to keep hot water circulation to minimum, not only for efficiency, but also to minimise risk of overheating, which is theoretically an issue now the barns have been internally insulated and in some cases, given quite a bit of glazing. “We have made sure there is lots of potential to open windows, too,” Hannah added.

Mechanical ventilation with heat recovery is part of the energy strategy, as well as ensuring a comfortable and healthy indoor environment. MVHR ensures humidity control, which is important in an internally insulated building. As is often the case, retrofitting MVHR ductwork into a historic building like this was not all straightforward, as Hannah explained:

“It was pretty challenging to design and install, as there really are not many places the duct runs can go, especially in a couple of the houses where the ceilings are already very low – and some have vaulted ceilings upstairs.” Jonathan concurs: “It was complicated getting all the ductwork to fit into the old building. The MVHR installation was probably the hardest part of the build.”

The heating would also have to more or less run itself – occupants staying only a few days don’t get the chance to familiarise themselves with the controls. Because underfloor heating is slower to respond than a conventional radiator system, there is always a danger that people unfamiliar with it will tend to overshoot when they alter the thermostat, Hannah Jones explained. So the control strategy is to give the occupants no control over main underfloor heating system, but just keep it running at a steady 20 degrees.

Instead of altering the thermostat, guests have the option to light a woodburner or turn on electric towel rails if they want an extra boost of heat.

For the same reason, the heating will only be set back a couple of degrees when units are empty, so it doesn’t take too long to heat them up again. “This is all being fine-tuned as we are commissioning the barns over this winter. They started off super cosy – we have been going round turning it all down bit by bit – and will go on fine-tuning as we get feedback from visitors.”

The approach of the contractor on a sensitive job like this will make or break the final result. Hannah and Jonathan agreed that the contractor here – local firm Corinium – was an excellent appointment.

“The contractors and subcontractors were great, and there is a really good level of installation,” Hannah said. “We explained the rationale for the details to them, and they were really good at identifying where a particular approach might be needed, and checking back with us.

“The electrician was really on the ball and picked up what things needed to be thought about, which was very helpful as the job moved along very quickly. It was really good to have a contractor on site who was so mindful of what they were doing.”

Work of this quality is never cheap, and a very high standard of interior decoration – evident in the photographs – has cemented the luxury feel. George says the investment was substantial, but he hopes to make a return over the years to come.

As Jonathan put it: “I think the great thing about this client is that they were looking at an asset for the family, for the long term. If they had been converting it to sell, they might have been more ruthless and not done the job the same way – but they are taking a longer view.”

George says that the comfort levels achieved in the barns are better than he had dared to hope: “I’m amazed by how warm they are! One of my biggest concerns with the heat pump was – how flexible would the heating be? It runs at a low temperature, so I worried that it would take three or four days to warm them up.

“However the barns are remarkably well insulated, so what I hadn’t appreciated was that when I went to turn the heat up, the buildings would already be warm, so it didn’t take long to get them to temperature at all. In fact I had it set at 23 and it was too warm, we’ve had to turn it down! It’s very different from my house where I whack the oil heating up to about 30 for a couple of hours, then it cools right down again while we are out.”

Laughing, he added: “The barns are far more comfortable than my house. Maybe one day I’ll be able to move into one!”