The problem

Q: “We want to build a development of homes right now, to meet the 2025 Future Homes Standard. We don’t want to use gas, but we’ll need to stay within the capital costs and running costs for gas-heated homes. How are we going to do this?“

A: “With Passivhaus.”

The client was clear from the outset about wanting to meet the Future Homes Standard, and to be gas free. They were aware Passivhaus would be a good way to meet this brief, and would offer performance guarantees, and comfortable and healthy homes. But they were not confident that they could get their regular contractors to sign up.

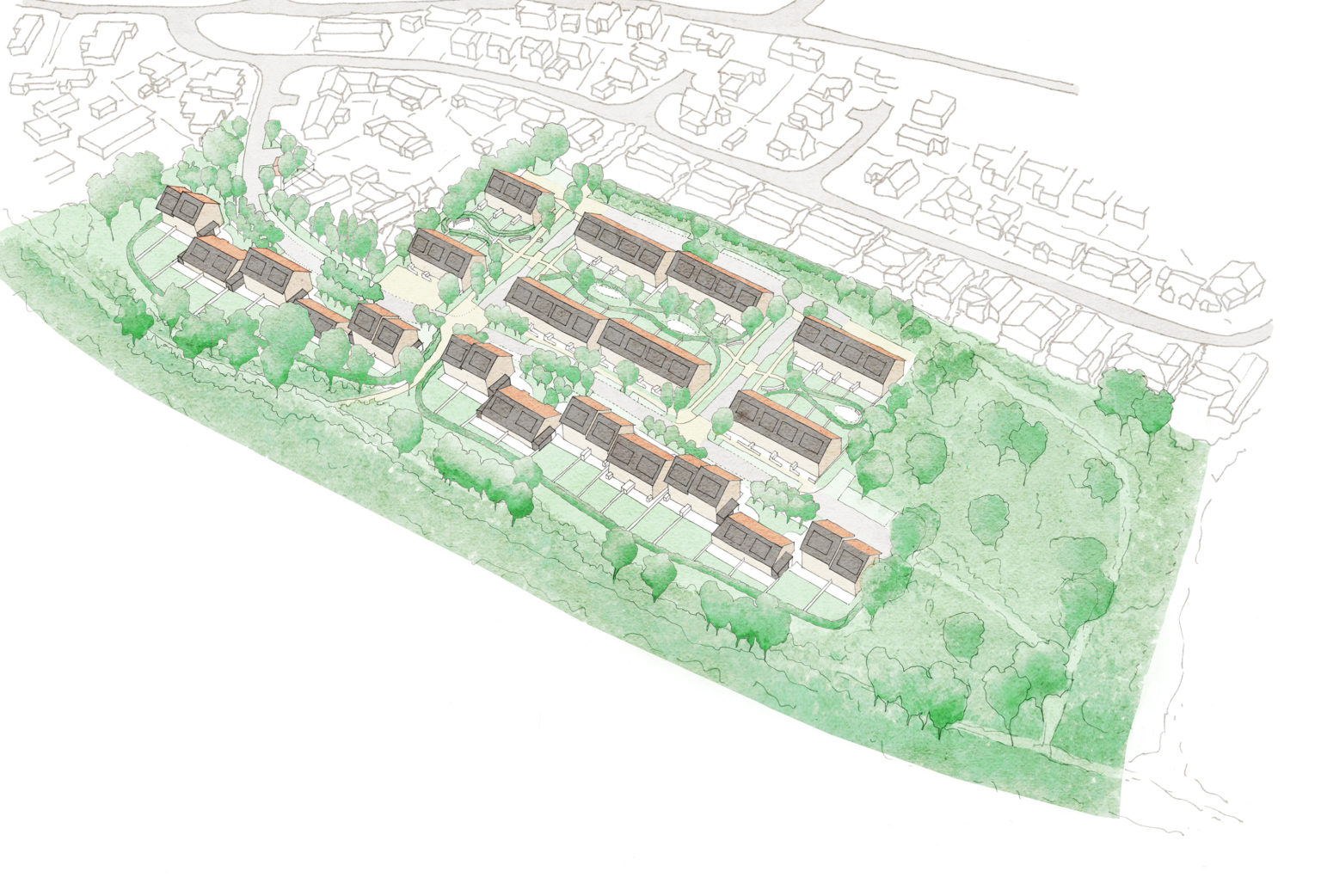

North Somerset Council has just secured planning approval for a 52-home development on council-owned land on the edge of Nailsea, that is set to meet all these criteria. Some will be let at a fixed affordable rent, and some sold on the open market. Either way, the client can’t expect a price premium.

The solution

We believe Passivhaus is the most effective route to achieving the Future Homes Standard and ensuring buildings can be zero carbon, delivering comfortable, healthy and high-quality homes in the process.

The secret to North Somerset’s success lay in getting the right advice from the start.

The scheme’s architects are Mikhail Riches – famously winners of the Stirling Prize for Architecture, for the design of the Goldsmith Street Passivhaus development in Norwich. Greengauge were M&E consultants for Goldsmith Street, and were included as consultants in the architect’s successful competition entry to design North Somerset’s scheme.

This time Greengauge are working as both Passivhaus-qualified energy consultants and as building services designers – roles that are quite often separated.

As Greengauge’s Adam Lane explains “The local authority client was open to Passivhaus, but it took a little while for Passivhaus to be agreed. There were commercial concerns – the client didn’t want to put off their pool of framework contractors. “

However, Greengauge knew that the right shaped building, facing the right way, can achieve a very low heating demand and high comfort with a relatively straightforward construction.

Key stats

“Greengauge’s input helped steer design decisions in the direction of efficiency and buildability early on, before planning permission had fixed the design. This enabled a successful design that is fundamentally economical of energy.”

What we did

The first step was to establish that contractors would be comfortable with an elemental performance (U-values, airtightness and the like) that could work with Passivhaus. Greengauge could then work with the client and architect to develop the shape and orientation of the buildings, to optimise performance within the constraints of a construction system contractors were confident with.

“Fairly early in the process we ran a competition for a construction system. One reason for doing this was because the initial funding from Homes England required an element of MMC (modern methods of construction, i.e. offsite construction) so we wanted to explore this with contractors. And at the same time, we linked the criteria for the system to the U-values and air tightness we felt would work for Passivhaus,” Adam explains.

“We got feedback that timber framers were happy to meet these standards. The good response to this competition allayed some of the client team’s fears and made Passivhaus less of a worry.

The next step was to refine the designs, to get the performance right for all the house types.

“While the major design decisions were still being made (ie pre-planning) we were able to make some valuable changes to the original plans, which made a big difference to performance,” Energy consultant Mitch Finn explains.

“At the start, the layout had the houses clustered in little closes or courtyards, with the homes facing in various directions.

“This kind of layout doesn’t work well in terms of optimising solar gain and limiting overheating. It is much more favourable to have a north/south orientation where the site permits ––and here there is a gently sloping site open to the south, so it made a lot of sense to take advantage of this.

“Reorienting the houses gave us access to more solar gains, giving reduced energy use without additional construction costs.”

Mitch also advised some additional tweaks, such as matching house types within the terraces to reduce areas of exposed gables.

The aim was to reduce form factors (the ratio of outside surface area to useful internal floor area) to around 3 or below. This keeps construction simple. “Above 3.5 you have to do a lot more work with the fabric and detailing, to get the same performance.” This can add considerable expense, so is well worth avoiding.

Rather than design and analyse every element of the construction in detail – the process needed for final certification – at pre-planning the task is to ensure that all the “worst cases” can still comply with the Passivhaus standard. This establishes the feasibility of Passivhaus – and the likely maximum energy requirements – across the whole development.

At this stage Passivhaus certification for the small number of bungalows on the site was ruled out: to meet Passivhaus with the poor form factor inherent to any single storey building, would have required a different and more expensive construction system. Instead these are set to achieve the Passivhaus Institute Low Energy Building Standard.

Among the two-storey houses, Greengauge identified those house types most likely to be at risk of either higher heat demand, or higher overheating.

The house types with highest heat demand would be those with their larger, garden-facing glazing areas oriented north. North glazing loses more, and gains less, heat than its opposite, so it is important for energy efficiency not to have too much of it. Smaller units (the smaller pairs of semis) were likely to have higher heat demand than the larger units and short terraces, because of their higher surface area/floor area ratio.

All the house types tested passed the Passivhaus heating demand criterion on the basis of a peak heating load of 10 W/m2 (on the typical coldest two days of the year) – one of the ways to meet the Passivhaus standard for space heating.

Some just failed to meet the 15kWh/m2 alternative target, because they had lower levels of solar gain over the year.

But heat loss over the year is important too: “We cannot lose sight of kWh/m2.a because that is the important metric for the tenant – it represents their bills,” Mitch says. However, the ‘worst’ houses were only a couple of kWh/m2.a above 15 – this represents just a small percentage of a typical home energy use for heating, hot water and all lighting and appliances over a year.

For an overheating check, a different set of “worst case” options was modelled:

Passivhaus sets a limit on overheating defined by the percentage of hours in the year that the home is predicted to sit at above 25 degrees.

The homes most likely to overheat are going to be those with larger areas of south, east or west glazing (east and west glazing can be problematic because the sun is lower, so is harder to shade out with eaves or overhangs).

But it is also important to know how many people will be living in the space, contributing to the overall heat load that might be building up indoors.

The Passivhaus calculation software has a built-in occupancy rate per m2 of space, related to generous German space norms. British housing can be a great deal more densely occupied – and with more occupants, comes more internal heat gain. Everyone will be contributing body heat, appliance use (cooking, kettles, TVs/computers/X-box etc), and also hot water use.

British Passivhaus designers need to be alert to this. In some cases, the maximum occupancy as determined by the numbers of bed spaces in the Nailsea homes, was as many as three times the occupancy “built in” to PHPP (the Passivhaus calculation software). So Greengauge also looked at the summer performance of those homes which had the highest maximum occupant density, in the scenario that they were fully occupied.

Greengauge also applied a conservative assumption to the use of blinds and window opening by occupants – basically, none. A potential mistake with overheating assessments is to assume occupants have thrown open all the windows, and they leave the patio doors open all night, and – hey presto, no overheating.

No-one actually lives like this though: people go out, people lock up at night, people get fed up with the smoke from next door’s barbecue. So they might shut the windows even on a scorching hot day.

To make sure occupants will still be comfortable even with hatches all battened down, Greengauge tested a scenario for summer performance based on cooling via the ventilation system only (plus the built-in shading via the eaves and window overhangs), with all windows shut, and no closing of blinds or curtains.

“This is an important calculation to do, because you can’t predict people’s window opening behaviour,” Mitch explains.

Happily, the relatively simple houses – with no extravagant floor–to-ceiling glazing ( a common driver of overheating problems) – all passed the Passivhaus requirements of less than 10% of the year above 25 degrees with these conservative window and shading assumptions. They all also passed the ‘good practice’ recommendation of above 25 degrees for 5% of the year or less. The highest overheating score on the conservative scenario was 3.6% of the year above 25 degrees.

Greengauge also calculated the hours of overheating with some extra ventilation, eg windows ajar, or windows wide open for a couple of hours, to show how much difference effective window ventilation can make.

Modelling suggested that if occupants used their windows judiciously, the hours above 25 degrees in a typical year could be kept down to only a fraction of a percent at most – so all occupants ought to be able to stay very comfortable all through the summer.

Building services

Electricity is already lower-carbon than mains gas in the UK, and it is continuing to decarbonise, as large-scale renewables such as offshore wind are being added to the generation mix, and coal and gas phase out. So it is an obvious choice for heating a low-carbon development.

Electricity is however a lot more expensive per unit of heat than the current price of gas (around three times) so electric heating has a justified reputation for being expensive.

The usual solution proposed to tackle this issue in low carbon homes, is the use of heat pumps. These produce around three units of heat for each unit of electricity consumed – at a stroke, slashing heating bills, and cutting emissions still further.

The snag is that heat pumps (and the larger radiators they work with best) are a lot more expensive to install than a standard gas-fired heating system. But there was nothing extra in the budget. “We were working within a QS cost plan that was drawn up on the basis of gas heating and hot water, so there were quite strict limits on capital expenditure,” Greengauge building services designer Adam explains.

However, he saw a clever way out of this dilemma.

In Passivhaus, the space heating load is actually a very small proportion of the overall energy use of the home – and even, considerably smaller than the heat load from the hot water. (This is not least because in a Passivhaus, space heating is only needed for a few months of the year, while people need showers all year round.)

A heat pump for space heating needs to produce a fair amount of heat at once, even in a Passivhaus: it has to be able to cope even in a “beast from the east” type scenario. It will be doing most of its work in just the coldest weeks of the year. This sets a minimum size, and therefore a minimum cost, for a system.

A heat pump heating the hot water however, can chug away steadily all the time; whether people are at home or not, whether they are asleep of not, and save up a tankful of hot water for when its needed.

A heat pump that only heats the water tank can therefore be relatively small, simple and inexpensive. The air supply it needs does not require a fan set outside the house (the standard arrangement with an air source heat pump for space heating). Instead, it can draw air in though a duct in the wall, extract some ambient heat, and blow the cooled air back out through a second duct.

This means there is no equipment and very little noise outside, removing any need to assess the look or the sound from the garden or from next door. And heat pumps like this come in a simple, ready to install unit integrated with the hot water cylinder, so they make life easier on site too.

As the hot water is actually the larger load, the hot water heat pump makes a large dent in energy use and emissions – and in bills. (To make the heat pump’s job a little easier, waste water heat recovery is also proposed – these can recover up to 50% of the heat that goes down the drain when you shower.)

The relatively small residual load for space heat can be covered with electric radiators: cheap, simple, and not unlike a typical gas–heated domestic radiator – so familiar too.

Carefully costing out this option showed the team that this mixed approach could hit all three of their important targets: the energy and emissions target, the build cost/complexity target, and the affordability target.

While householder bills would be a little higher with electric radiators that they would have been with an all-heat-pump build, the heating demand is low enough that the difference in heating bills would be on average less than £1 a week, Greengauge calculated (based on the modelled space heating demand and an estimated p/kWh at the time).

As well as being the largest single load, hot water is also the load that varies between households, and is hardest to predict. Using a heat pump for hot water offers important protection from high bills for households with high hot water use.

And the build cost savings were instead being sunk into the fabric: it meant the householders would be living in a Passivhaus – with all the advantages of comfort and health relative to a non-Passivhaus home.

“The investment has gone into the fabric. The fabric is doing the heavy lifting” This is far and away the most robust approach to keeping bills low, Adam points out.

While the radiators will seem familiar, the hot water will require different approach to what most people are used to for new homes. Some may be unfamiliar with the idea of a hot water cylinder at all. The heat pump is small so only trickles heat in gently, meaning the water heat-up needs time. The systems does suit itself very well to overnight charging on a low tariff – and will be set up to take free electricity from the solar panels, as well.

“We’ve got used to combi boilers, but councils are starting to understand that hot water cylinders are going to be coming back”, Adam says.

The gentle, incredibly low carbon heat that heat pumps produce best, doesn’t work like a combi boiler, sitting there doing nothing most of the time, then blasting out a massive stream of heat when someone decides to have a shower. Efficient, effective decarbonisation requires us to use renewable energy when it is available and store it for when it is needed.

In-house collaboration

It isn’t unusual for the building’s services and the energy modelling for a design project to be undertaken by separate teams.

But Greengauge found that taking on both roles within their firm was very beneficial. The energy modeller needs to understand what kind of systems they are working with, their losses and their gains, and what if any renewable energy is going to be available. And the building services designer certainly needs to know exactly what the heat load are going to be – across the year, and also in the worst weather.

Without certainty over these figures, the temptation for building series engineers is always to “put in a bigger one” as Adam Lane explains:

“All too often building services engineering ends up being the king of oversizing – it’s kind of the nature of the industry, if you don’t put in double what you think you need, there might not be enough heat and then the client will sue.”

That kind of fear can inhibit a tighter, more economical design, Adam explains. “With Passivhaus, the reassurance PHPP gives you is that you really do know what the loads will be, and so you do not feel you are taking a risk. And when the Passivhaus analysis is in-house, you have access to all the calculations, you can look right into the numbers and discuss them. It makes it so much easier to design out waste.”

“We work together and have access to each others’ calculations, which makes progress much smoother. It’s an integrated way of working, and great for us individually too, as we learn from each other throughout the process. Communication is easy, so there’s a lot of cross-pollination”

Adam knows that the ultimate occupants will be getting homes that perform as they should – but given that most people don’t really know what Passivhaus is, he doesn’t expect the open market homes will be advertised at a premium.

He does however believe they should understand they are getting an exceptional product – even though the build cost is not expected to be exceptional at all.

Greengauge’s input helped steer design decisions in the direction of efficiency and buildability early on, before planning permission had fixed the design. This enabled a successful design that is so fundamentally economical of energy, that familiar and low-cost technologies will deliver excellent overall performance. The best of modern low-carbon technology has been used, but judiciously, where it really pays its way in energy terms. A large share of the work is done by simple decisions around shape and orientation.

This combination has ensured that the dwellings can meet the exacting brief set by the client, and also those required for Passivhaus, will guarantee low bills and high comfort to occupants, and still remain within the original construction budget.