The problem

It is easy to imagine falling in love with a beautiful, rambling Tudor manor in the Cotswolds. Less easy perhaps, to imagine living there. Yet one family fell so hard for this stunning, Grade I listed, 20-roomed house that they decided to do exactly that. They bought it, and are making it their family home.

The house was built in several stages over 15th, 16th and 17th centuries. It still retains the original mediaeval dining hall – open to the oak-trussed roof – and magnificent open fireplaces you could roast a hog in.

But comfortable it wasn’t. Despite the three oil boilers roaring away in the basement, temperatures of 12 degrees indoors were not unheard of; Christmas dinner in the historic hall was “absolutely freezing”.

Somehow the family needed to transform the comfort, while preserving pretty much everything about the fabric and appearance that they loved so much. They really didn’t want to install a home cinema, or en-suites with jacuzzis in every bedroom. They did however want to be warm.

As soon as they could, the client consulted architects MHWorkshop, and building engineers Greengauge, to give expert advice on the building and the work they might need to do.

Greengauge’s first task was to find out how the existing heating system was performing, and whether it could be modified to improve the comfort, or if the whole system would need replacing – a daunting prospect in a Grade I listed building

The heating system was “decrepit”, with a mish-mash of radiators and some fan coil units, all installed piecemeal over the past 20-30 years. These were served by oil boilers of a similar vintage. There were also a number of electric heaters dotted around some of the coldest spaces.

The solution

In order to get the measure of the building and its heating system, Greengauge set up extensive monitoring – of the heating system, and the room temperatures it was achieving throughout the house

Monitoring was carried out during February and March. The weather was cold, but not exceptionally so; outside temperatures were mostly between 1 and 10 degrees. With the heating running as normal, some of the rooms edged up towards around 20 degrees. But many others barely made it to 16.

The old heating system had weather compensation incorporated into the controls, and this was reducing flow temperatures, so Greengauge disabled it and ran the heating at 80 degrees. This improved matters – but the house still wasn’t warm.

Analysis of the flow and return temperatures made it clear that the heat was not getting out into the rooms fast enough. The house was cold because there just weren’t enough radiators. A new system would be needed.

The monitoring and analysis was important evidence to share with the planners and conservation officers, says Greengauge’s Oscar Garcia Mendez. “It showed that if we could not change the heating system, and fully replumb the house, we would not be able to make the house any warmer.”

The conservation officer was understanding, which was a relief to everyone. “We had a good conservation officer,” Hannah Jones recalls. “We took our findings and our proposals for a new system to the pre-app meeting and they were reasonable, and didn’t push back on everything.”

The officer agreed to allow the client to replace their heating system, even though that meant fully replumbing the house.

Key stats

“The monitoring and analysis we undertook was important evidence to share with the planners and conservation officers. It showed that if we could not change the heating system, and fully replumb the house, we would not be able to make the house any warmer.”

Low carbon heat

Options for improving the fabric performance were extremely limited. Roof renovation meant more insulation could be added, and there was scope for some draught-proofing. But otherwise, neither clients nor conservation officers wanted more substantial alterations to the fabric.

Nonetheless, the output of the three 30-year-old oil boilers in the basement plant room would go a good way to meeting the estimated 165 kW peak heat load. But they were oil – polluting and very high carbon. Not only that, they were noisy and smelly, and the occupants wanted them out.

A heat pump would be much quieter, and not smelly at all – as well as being a lot lower-carbon. With extensive grounds, a ground-source pump was a definite possibility. To get a feel for how practicable this would be as a replacement heating, the Greengauge team turned the boiler temperatures down to 45 to mimic the output of a heat pump operating at reasonable COP. The house was very very cold. Even allowing for installation of extra radiators, it was clear that the house could not be heated this way.

Did this mean the end of the heat pump idea? Well there is one way to sneak a giant emitter into a historic building, and that is under the floor. Some floors were having to be lifted for repairs anyway, and others could relatively neatly be taken up and replaced, or topped with a floating-floor underfloor heating system with integral insulation.

However, they also had to find a big enough heat source. Despite the extensive grounds, the steep slope and rocky ground meant there wasn’t space for a coil collector, so boreholes were the better option. However, even this would be restricted, as only the areas alongside the entrance road were accessible to the boring machinery. They were also required by the conservation officer to check none of the drilling points were archaeologically sensitive (as well as the historic manor gardens which themselves date back to Tudor times, there are prehistoric earthworks in many surrounding fields).

The surveys suggested only around 50-60 kW of borehole capacity could be fitted into this limited space (though in the event, the ingenuity of the installers managed to make it to 80kW). The combination of this capacity restriction and the limited improvements possible to a very hungry fabric, meant that it was not going to be possible to do without fossil fuel altogether, and oil boilers would still be required.

To make the most on the scope for low carbon heat, while not over-complicating the (already quite complicated) distribution and controls, Greengauge opted for a two-mode, two-source heating system.

When temperatures are cool rather than cold, the heat pump will carry the full load of the heating, with the oil boilers only responsible for hot water. The pump will heat the floors and radiators to around 45 degrees, which will ensure a good coefficient of performance, but make all the difference indoors. When the cold really starts to bite (when the outside temperatures are below about 12 degrees), the oil boilers will take over the radiators so the flow temperatures can be increased, with the heat pump topping up the comfort via the under-floor circuits.

The ‘shoulder seasons’ in this house are expected to take up a significant proportion of the year. The house does not receive a huge amount of solar gain though its medieval windows, and the thick stone walls have direct thermal connection to the ground. “We visited one lovely day when it was about 28 degrees outside – it was still cold inside,” Hannah Jones recalls. This means the heat pump heating season is expected to be long.

Client priorities and informed choices

Even with permission to install a new heating system, including a number of new radiators, getting the whole house up to 20 degrees in the coldest weather would be challenging.

And although the planners had given the go-ahead, the clients themselves were cautious about adding new radiators – even ones that pretty much matched the existing traditional-style cast iron ones already in place.

Rather than make a guess on the client’s behalf, Greengauge involved the client closely in the final heating system design. The detailed system monitoring he had done enabled Oscar Garcia Mendez to work through a number of iterations with the client, involving radiators of different specs and sizes, modelling the heating implications of each, so the client could make their own choice about the balance between aesthetics and comfort. The client decided how much cold they were willing to accept in the dead of winter, in return for keeping intact the interior they had so much fallen in love with.

The clients finally settled for an arrangement that should keep most of the rooms at a comfortable 20 degrees, even when temperatures outside drop below -5. But there are some particularly historic rooms where they have opted for minimal change. In really cold weather (-5 degrees outside) these rooms will probably only get up to 18 or 19 degrees, or, in one particularly chilly bedroom, only 17 degrees. But this is acceptable to the client, as they love the rooms so much as they are.

Greengauge has also kept some options open if the cold gets a bit much – in the hardest-to-heat dining hall, additional concealed pipe tails were run to the room, so more radiators can be added in future.

Keeping the new system discreet

It is very hard to route pipeworks sensitively in a 15th century structure, and the previous system had left services visible. Greengauge and MHWorkshop worked hard together, in consultation with the conservation team, to install the maximum services with the minimum aesthetic disruption – and even improve the appearance where they could. Where floors needed lifting for repairs, for example, this enabled new concealed pipe runs, making the final layout tidier than the original: this was helpful in making the case for a new system.

Radial distribution kept runs short, and, importantly, allowed room-by-room control – given the size of the house, room by room zoning is essential in order to keep on top of energy consumption.

The new radiators match the “traditional” style of those already in place. As Hannah Jones explained, there were more aesthetically acceptable, but also more practical: “cast iron, high volume radiators do emit a little more radiant heat as well as heating by convection. This increases thermal comfort without drying the fabric as much as convection or blown air heating.”

In a few rooms there is also radiant heating with wood stoves, and the client did want to retain some of the huge open fireplaces. “We are definitely not worried about under-ventilation!”

Other than this though, there was no option for additional radiant heating as, by definition, you can’t conceal it.

In all, the team were able to very nearly double the emitter capacity to around 165 kW without creating any unacceptable changes.

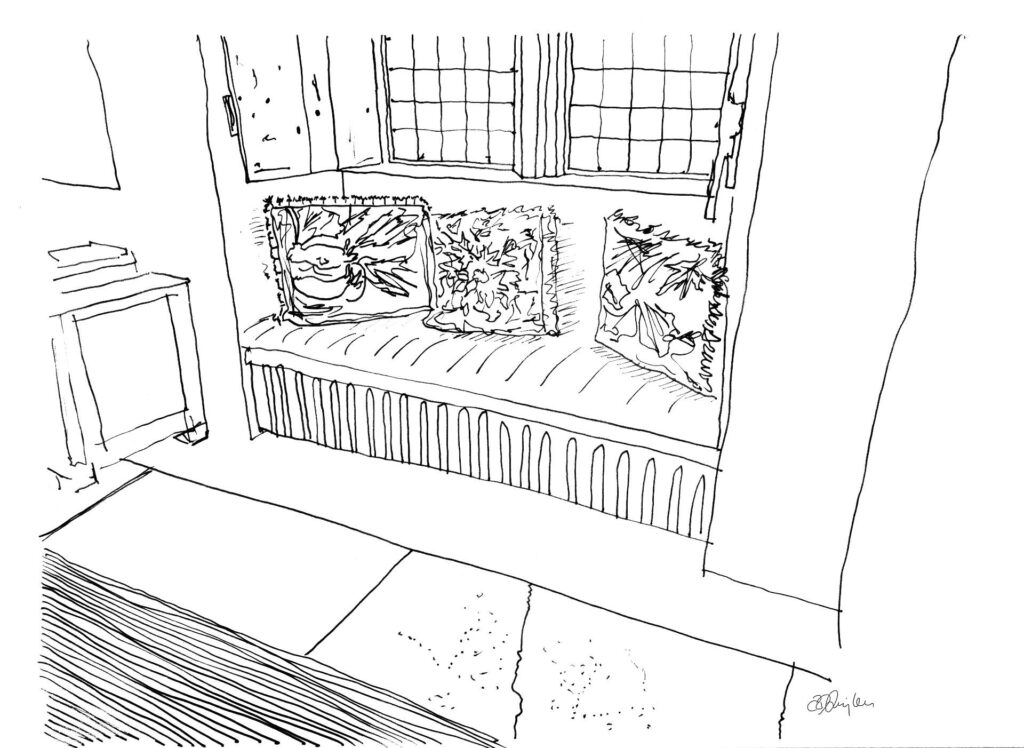

Many of the radiators are being installed under the window seats in the window recesses – an acceptably inconspicuous location. However, as is often the case with historic buildings, the neat panelled joinery of the window surrounds conceals rubbly and unfinished masonry beneath: “you could feel the cold air blowing through the cracks,” Hannah Jones recalls. As the area is behind panelling however, it will be possible to upgrade the fabric here without any visual impact. “Concentrating on insulating these concealed sections of wall and plastering the cracks should improve what would otherwise be very energy-wasteful locations for the radiators,” Hannah Jones says.

The wiring too needed updating, and once again, the new system is generally more discreet than the old one: some wiring was poorly concealed, or simply surface mounted. “Very detailed surveys by the architects mean we could plan much of the wiring to use the existing holes in the skirting boards for new sockets,” Oscar Garcia Mendez explains.

An outbuilding was repurposed as a plant room to house both the heat pump and the new oil boilers, with pre-insulated pipework carrying low- and high-temperature heat to the house for internal distribution.

The M&E contractor needed reassuring that the client really did not want to add new bathrooms everywhere – it was much more important to them to retain the character of the house as they found it. This meant it was possible to supply hot water relatively simply. The existing system already included three hot water tanks, so by upgrading these, most bathrooms and sinks could still be served directly, avoiding the large losses from continuously pumped heat, except for one run on a long corridor.

The work is now being completed. The extensiveness of the building means that contractors are able to work safely while social distancing, so – all remaining well on site – dinner next Christmas shouldn’t have to be eaten with woolly hats in place of paper crowns.

Read about our work on other Listed Buildings: A Georgian Town House, an early example of modular design and a listed concrete building development